By Henry Hing Lee Chan

Will European Banks Hold Cash and End Negative Interest Rate Policy?

The news that an increasing number of European banks are looking for cheap way to store cash as interest rates go negative is a good way for banks to register their protest over the impact of negative interest rates. Although the move is neither in the interest of the banks nor the central banks, the idea alone already signals the limitation of negative interest rates as a policy tool.

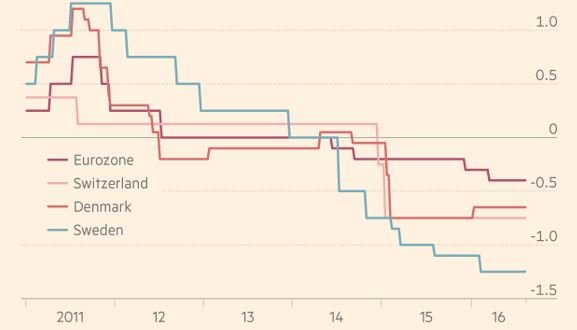

At the moment, four currencies in Europe are implementing the negative interest policy: the Euro, the Swiss Franc, the Swedish Krona and the Danish Krone (see Figure 1). After the European Central Bank’s (ECB) most recent rate cut in March, private sector banks are paying what amounts to an annual level of 0.4 percent on most of the funds they keep in the Eurozone’s 19 national central banks. The negative interest rate policy, which started in 2014, is intended to spark economic growth by forcing the banks to lend money out instead of holding it in their vaults. The practice of charging banks to pay for funds at the ECB has already cost the banks 2.64 billion Euros since the policy was adopted in 2014.

Figure 1. Negative Interest Rates in

Europe, Central Banks’ Policy Rates (%)

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream

European central bankers have indicated to the market that

they could cut interest rates again should economic conditions worsen, but the

move by the banks and insurance companies to hold cash instead of keeping money

at the central banks and pay the negative interest rates could well preempt the

future rate cut. If banks are not paying the central banks interest charges,

then they will not be affected by further official interest rate cuts and would

not be spurred to lend out money as what ECB planned.

The hoarding of cash creates a host of costs, the most

important of which are storage, transport, and insurance. The withdrawal of a

large amount of cash in one swoop would keep transport and storage costs low, but

the real sticky issue is insurance. At the moment, the insurance companies

charge 0.5 percent to 1 percent of the value of the banknotes stored. This

insurance premium is close to the negative 0.4 percent charge of the ECB and

that could well mean the room for further rate cuts by the ECB is probably

limited.

More

and more small banks in the Eurozone are charging retail clients with deposits

of more than 100,000 Euros in their account. How this will

affect the cash balances of such deposits in the banking system is also

important to the negative interest rate policy. If there is a mass withdrawal

by these clients from the banking system, that could also add pressure to end

the negative interest rate policy. At the moment, Euros in circulation and held

by banks add up to a total of 2.075 trillion, in which the banks hold 988

billion in their vaults and 1.1 trillion are in circulation.

There is little doubt that unconventional monetary policies

such as Quatitative Easing (QE) and negative interest rates had earlier helped

to stabilize financial markets and the economy. However, they are facing the

limitation of their policy effectiveness and signs of unintended collateral

damage are emerging. There are ongoing debates among economists on what the

next policy initiatives the governments can take to maintain economic buoyancy —

fiscal expansion or structural reforms? The market is watching the forthcoming

G20 meeting at Hangzhou to get a glimpse of the new economic thought.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *